Filters

Host (768597)

Bovine (1090)Canine (20)Cat (408)Chicken (1642)Cod (2)Cow (333)Crab (15)Dog (524)Dolphin (2)Duck (13)E Coli (239129)Equine (7)Feline (1864)Ferret (306)Fish (125)Frog (55)Goat (36847)Guinea Pig (752)Hamster (1376)Horse (903)Insect (2053)Mammalian (512)Mice (6)Monkey (601)Mouse (96266)Pig (197)Porcine (70)Rabbit (358709)Rat (11723)Ray (55)Salamander (4)Salmon (15)Shark (3)Sheep (4247)Snake (4)Swine (301)Turkey (57)Whale (3)Yeast (5336)Zebrafish (3022)Isotype (156643)

IgA (13624)IgA1 (941)IgA2 (318)IgD (1949)IgE (5594)IgG (87187)IgG1 (16733)IgG2 (1329)IgG3 (2719)IgG4 (1689)IgM (22029)IgY (2531)Label (239340)

AF488 (2465)AF594 (662)AF647 (2324)ALEXA (11546)ALEXA FLUOR 350 (255)ALEXA FLUOR 405 (260)ALEXA FLUOR 488 (672)ALEXA FLUOR 532 (260)ALEXA FLUOR 555 (274)ALEXA FLUOR 568 (253)ALEXA FLUOR 594 (299)ALEXA FLUOR 633 (262)ALEXA FLUOR 647 (607)ALEXA FLUOR 660 (252)ALEXA FLUOR 680 (422)ALEXA FLUOR 700 (2)ALEXA FLUOR 750 (414)ALEXA FLUOR 790 (215)Alkaline Phosphatase (825)Allophycocyanin (32)ALP (387)AMCA (80)AP (1160)APC (15217)APC C750 (13)Apc Cy7 (1248)ATTO 390 (3)ATTO 488 (6)ATTO 550 (1)ATTO 594 (5)ATTO 647N (4)AVI (53)Beads (225)Beta Gal (2)BgG (1)BIMA (6)Biotin (27817)Biotinylated (1810)Blue (708)BSA (878)BTG (46)C Terminal (688)CF Blue (19)Colloidal (22)Conjugated (29246)Cy (163)Cy3 (390)Cy5 (2041)Cy5 5 (2469)Cy5 PE (1)Cy7 (3638)Dual (170)DY549 (3)DY649 (3)Dye (1)DyLight (1430)DyLight 405 (7)DyLight 488 (216)DyLight 549 (17)DyLight 594 (84)DyLight 649 (3)DyLight 650 (35)DyLight 680 (17)DyLight 800 (21)Fam (5)Fc Tag (8)FITC (30165)Flag (208)Fluorescent (146)GFP (563)GFP Tag (164)Glucose Oxidase (59)Gold (511)Green (580)GST (711)GST Tag (315)HA Tag (430)His (619)His Tag (492)Horseradish (550)HRP (12960)HSA (249)iFluor (16571)Isoform b (31)KLH (88)Luciferase (105)Magnetic (254)MBP (338)MBP Tag (87)Myc Tag (398)OC 515 (1)Orange (78)OVA (104)Pacific Blue (213)Particle (64)PE (33571)PerCP (8438)Peroxidase (1380)POD (11)Poly Hrp (92)Poly Hrp40 (13)Poly Hrp80 (3)Puro (32)Red (2440)RFP Tag (63)Rhodamine (607)RPE (910)S Tag (194)SCF (184)SPRD (351)Streptavidin (55)SureLight (77)T7 Tag (97)Tag (4710)Texas (1249)Texas Red (1231)Triple (10)TRITC (1401)TRX tag (87)Unconjugated (2110)Unlabeled (218)Yellow (84)Pathogen (489613)

Adenovirus (8665)AIV (315)Bordetella (25035)Borrelia (18281)Candida (17817)Chikungunya (638)Chlamydia (17650)CMV (121394)Coronavirus (5948)Coxsackie (854)Dengue (2868)EBV (1510)Echovirus (215)Enterovirus (677)Hantavirus (254)HAV (905)HBV (2095)HHV (873)HIV (7865)hMPV (300)HSV (2356)HTLV (634)Influenza (22132)Isolate (1208)KSHV (396)Lentivirus (3755)Lineage (3025)Lysate (127759)Marek (93)Measles (1163)Parainfluenza (1681)Poliovirus (3030)Poxvirus (74)Rabies (1519)Reovirus (527)Retrovirus (1069)Rhinovirus (507)Rotavirus (5346)RSV (1781)Rubella (1070)SIV (277)Strain (67790)Vaccinia (7233)VZV (666)WNV (363)Species (2982223)

Alligator (10)Bovine (159546)Canine (120648)Cat (13082)Chicken (113771)Cod (1)Cow (2030)Dog (12745)Dolphin (21)Duck (9567)Equine (2004)Feline (996)Ferret (259)Fish (12797)Frog (1)Goat (90451)Guinea Pig (87888)Hamster (36959)Horse (41226)Human (955186)Insect (653)Lemur (119)Lizard (24)Monkey (110914)Mouse (470743)Pig (26204)Porcine (131703)Rabbit (127597)Rat (347841)Ray (442)Salmon (348)Seal (8)Shark (29)Sheep (104984)Snake (12)Swine (511)Toad (4)Turkey (244)Turtle (75)Whale (45)Zebrafish (535)Technique (5597646)

Activation (170393)Activity (10733)Affinity (44631)Agarose (2604)Aggregation (199)Antigen (135358)Apoptosis (27447)Array (2022)Blocking (71767)Blood (8528)Blot (10966)ChiP (815)Chromatin (6286)Colorimetric (9913)Control (80065)Culture (3218)Cytometry (5481)Depletion (54)DNA (172449)Dot (233)EIA (1039)Electron (6275)Electrophoresis (254)Elispot (1294)Enzymes (52671)Exosome (4280)Extract (1090)Fab (2230)FACS (43)FC (80929)Flow (6666)Fluorometric (1407)Formalin (97)Frozen (2671)Functional (708)Gel (2484)HTS (136)IF (12906)IHC (16566)Immunoassay (1589)Immunofluorescence (4119)Immunohistochemistry (72)Immunoprecipitation (68)intracellular (5602)IP (2840)iPSC (259)Isotype (8791)Lateral (1585)Lenti (319416)Light (37250)Microarray (47)MicroRNA (4834)Microscopy (52)miRNA (88044)Monoclonal (516109)Multi (3844)Multiplex (302)Negative (4261)PAGE (2520)Panel (1520)Paraffin (2587)PBS (20270)PCR (9)Peptide (276160)PerCP (13759)Polyclonal (2762994)Positive (6335)Precipitation (61)Premix (130)Primers (3467)Probe (2627)Profile (229)Pure (7808)Purification (15)Purified (78305)Real Time (3042)Resin (2955)Reverse (2435)RIA (460)RNAi (17)Rox (1022)RT PCR (6608)Sample (2667)SDS (1527)Section (2895)Separation (86)Sequencing (122)Shift (22)siRNA (319447)Standard (42468)Sterile (10170)Strip (1863)Taq (2)Tip (1176)Tissue (42812)Tube (3306)Vitro (3577)Vivo (981)WB (2515)Western Blot (10683)Tissue (2015946)

Adenocarcinoma (1075)Adipose (3459)Adrenal (657)Adult (4883)Amniotic (65)Animal (2447)Aorta (436)Appendix (89)Array (2022)Ascites (4377)Bile Duct (20)Bladder (1672)Blood (8528)Bone (27330)Brain (31189)Breast (10917)Calvaria (28)Carcinoma (13493)cDNA (58547)Cell (413805)Cellular (9357)Cerebellum (700)Cervix (232)Child (1)Choroid (19)Colon (3911)Connective (3601)Contaminant (3)Control (80065)Cord (661)Corpus (148)Cortex (698)Dendritic (1849)Diseased (265)Donor (1360)Duct (861)Duodenum (643)Embryo (425)Embryonic (4583)Endometrium (463)Endothelium (1424)Epidermis (166)Epithelium (4221)Esophagus (716)Exosome (4280)Eye (2033)Female (475)Frozen (2671)Gallbladder (155)Genital (5)Gland (3436)Granulocyte (8981)Heart (6850)Hela (413)Hippocampus (325)Histiocytic (74)Ileum (201)Insect (4880)Intestine (1944)Isolate (1208)Jejunum (175)Kidney (8075)Langerhans (283)Leukemia (21541)Liver (17340)Lobe (835)Lung (6064)Lymph (1208)Lymphatic (639)lymphocyte (22572)Lymphoma (12782)Lysate (127759)Lysosome (2813)Macrophage (31794)Male (1617)Malignant (1465)Mammary (1985)Mantle (1042)Marrow (2210)Mastocytoma (3)Matched (11710)Medulla (156)Melanoma (15522)Membrane (105772)Metastatic (3574)Mitochondrial (160319)Muscle (37419)Myeloma (748)Myocardium (11)Nerve (6398)Neuronal (17028)Node (1206)Normal (9486)Omentum (10)Ovarian (2509)Ovary (1172)Pair (47185)Pancreas (2843)Panel (1520)Penis (64)Peripheral (1912)Pharynx (122)Pituitary (5411)Placenta (4038)Prostate (9423)Proximal (318)Rectum (316)Region (202210)Retina (956)Salivary (3119)Sarcoma (6946)Section (2895)Serum (24880)Set (167654)Skeletal (13628)Skin (1879)Smooth (7577)Spinal (424)Spleen (2292)Stem (8892)Stomach (925)Stroma (49)Subcutaneous (47)Testis (15393)Thalamus (127)Thoracic (60)Throat (40)Thymus (2986)Thyroid (14121)Tongue (140)Total (10135)Trachea (227)Transformed (175)Tubule (48)Tumor (76921)Umbilical (208)Ureter (73)Urinary (2466)Uterine (303)Uterus (414)Understanding DNA Strand Separation in Crowded Cellular Environments: Why It Takes More Force

Explore how molecular crowding impacts DNA strand separation. Learn about biophysical insights from in vitro models and their relevance to cell biology.

Genprice

Scientific Publications

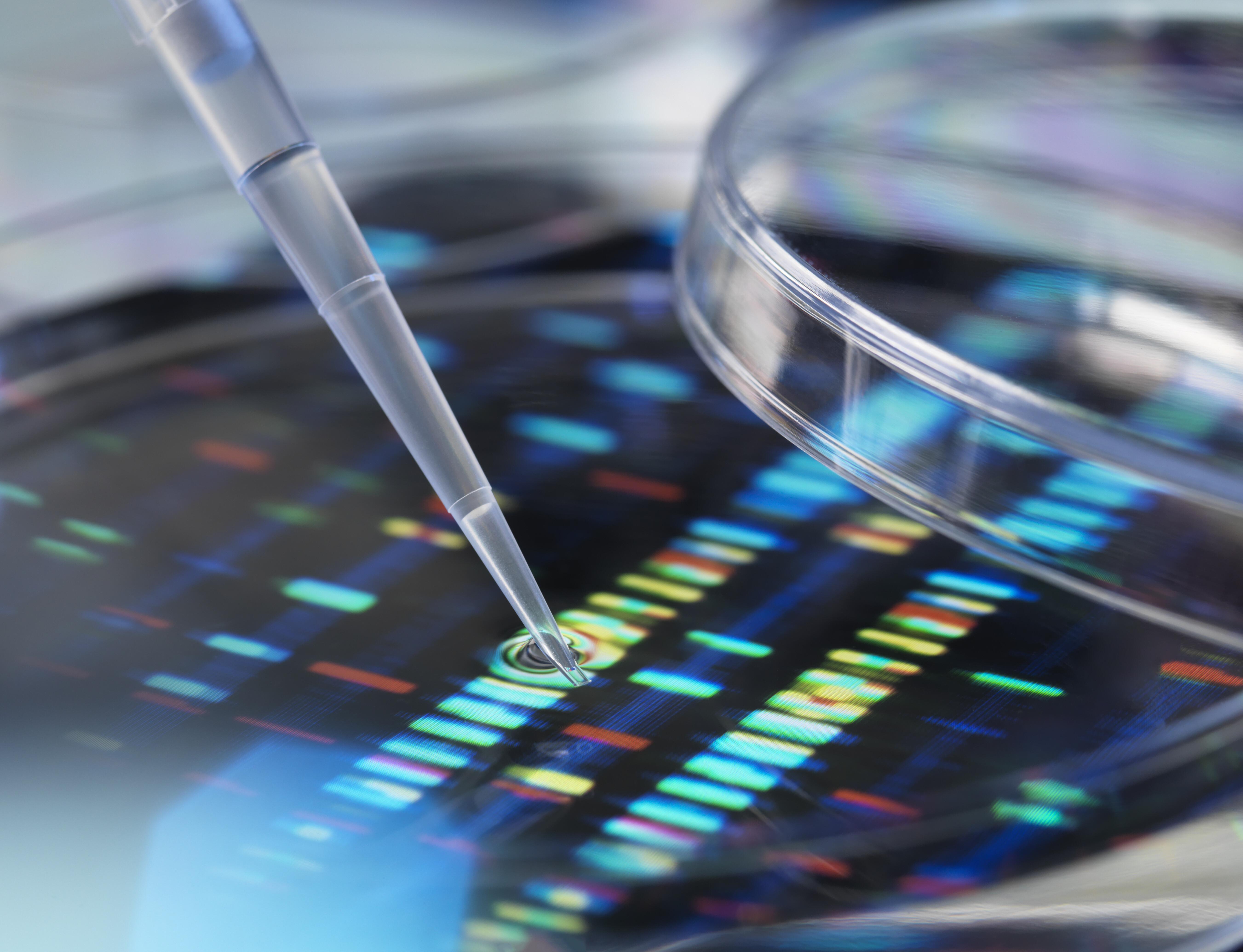

Understanding DNA Strand Separation in Crowded Cellular Environments: Why It Takes More Force

Introduction

DNA strand separation is a fundamental step in many biological processes, including replication and transcription. In simplified laboratory conditions, this process appears straightforward. But inside a living cell, the situation is very different. Recent studies have revealed that DNA strand separation actually requires more force in crowded cellular environments than in diluted solutions. This blog explores the scientific reasoning behind this observation and its broader implications.

What Is DNA Strand Separation?

DNA consists of two complementary strands wound around each other in a double helix. For processes like replication and gene expression to occur, these strands must be pulled apart—a process commonly called DNA unwinding or strand separation. This is typically performed by specific proteins, such as helicases, that exert mechanical force to split the strands.

Molecular Crowding Inside Cells

The intracellular environment is highly crowded. Unlike test tube experiments, the cytoplasm is packed with macromolecules such as proteins, RNA, ribosomes, and membrane structures. This state is referred to as macromolecular crowding, and it significantly influences molecular interactions, diffusion rates, and structural dynamics.

Crowding agents can range in size and shape and can either hinder or enhance molecular reactions depending on the physical context. In the case of DNA separation, crowding presents an additional layer of resistance.

Why Crowding Increases the Required Force

Recent experimental models that mimic the crowded cellular environment have shown that strand separation becomes mechanically more difficult. Here's why:

- Reduced Free Volume: The dense environment limits the physical space available for DNA strands to unwind and extend.

- Viscous Drag: The viscosity of the medium increases, which imposes additional frictional resistance on the separating strands.

- Excluded Volume Effect: Molecules that are not directly involved in DNA processes can still exert entropic pressure, making it harder for the DNA to change shape.

These physical barriers collectively demand greater force to unwind the double helix, even if the biochemical mechanism remains unchanged.

Laboratory Simulations

Scientists have replicated these crowded conditions using crowding agents like polyethylene glycol (PEG), dextran, and Ficoll in in vitro experiments. These agents mimic the packed nature of cytoplasm and allow researchers to measure how force thresholds shift under crowding.

One widely used technique is optical tweezers, which enable the direct application of pico-newton scale forces to single DNA molecules. The data clearly show that more force is needed to separate DNA in the presence of crowding agents compared to in diluted buffer solutions.

Broader Applications

Understanding the mechanical effects of crowding can benefit various research areas:

- Synthetic biology: Design of DNA-based nanodevices must account for environmental resistance.

- Molecular modeling: Improved simulation tools must include parameters for crowding to better predict behavior in living cells.

- Biomaterials engineering: The behavior of DNA and RNA in gels and other polymer matrices can inform the design of smart materials.

Conclusion

The discovery that DNA strand separation requires more force in crowded environments emphasizes the complexity of cellular life. It shows that physical conditions are just as important as chemical factors in molecular biology. As we continue to mimic and study these conditions, our understanding of biological systems will become more refined, leading to improved tools and technologies.